Greta Magnusson Grossman and the Grasshopper Lamp — Swedish Craft Meets American Industry

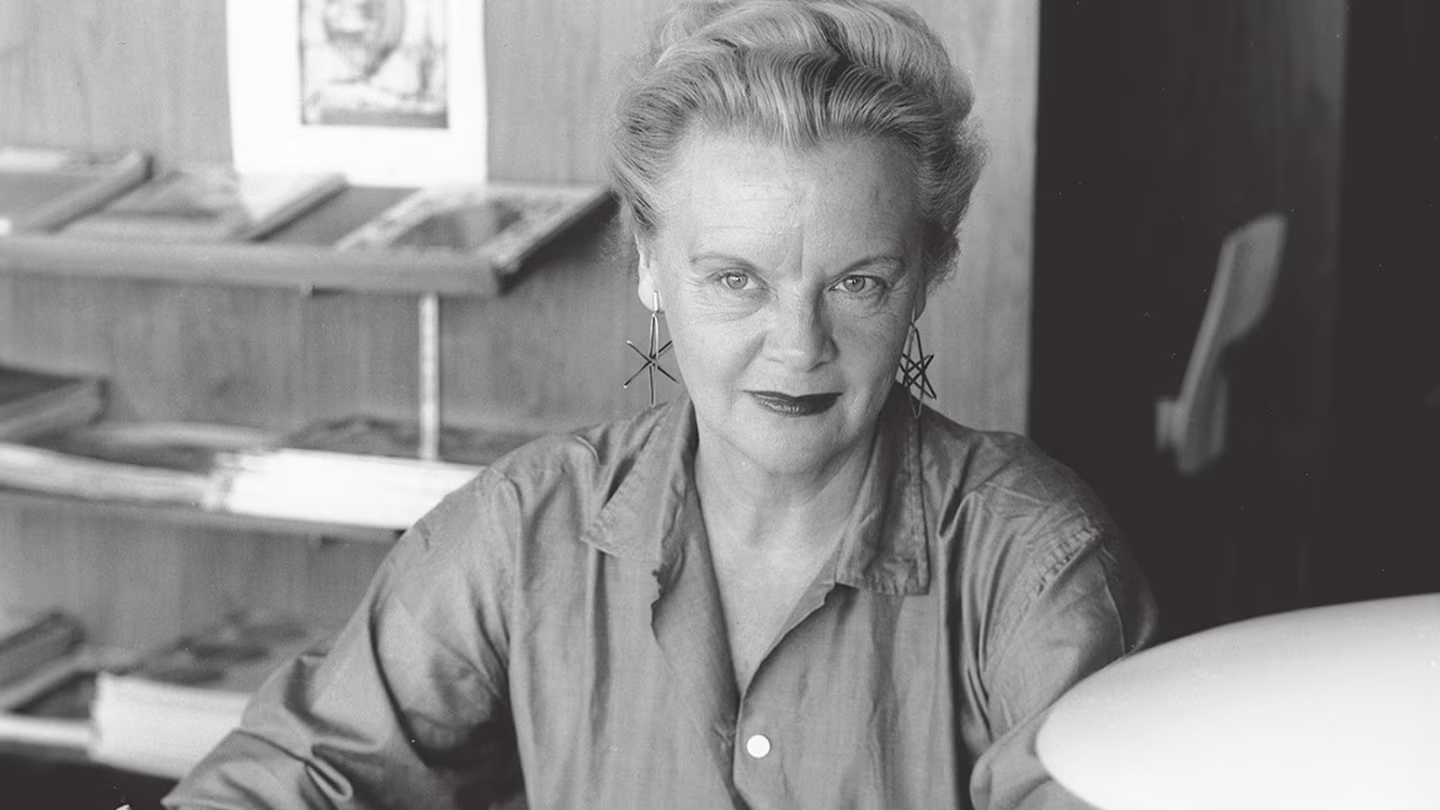

Greta Karin Ingeborg Magnusson Grossman (1906–1999) occupies a distinctive position in twentieth-century design history as a Swedish modernist who established her practice in Los Angeles and became a defining figure in California’s postwar design culture. Working as both architect and industrial designer from the 1940s through the 1960s, she produced furniture, lighting and interiors that merged Scandinavian craft traditions with American industrial production and the particular spatial and climatic conditions of Southern California. Her work remained largely overlooked for decades following her retirement but has been substantially re-evaluated since the early 2000s, with major furniture pieces reissued and her contribution to transatlantic modernism increasingly recognised.

Swedish Formation and Craft Training

Grossman was born in Helsingborg on 21 July 1906, daughter of Johan Magnusson, a bricklayer, and Tilda Magnusson (née Ekberg). Her background was working-class — a formation that shaped her pragmatic approach to design and her understanding of construction methods. She served an apprenticeship as a cabinetmaker at Kärnans möbeltillverkningsfirma in Helsingborg, receiving direct training in joinery, material properties and workshop practice. This craft foundation proved essential: unlike many designers who came to furniture through art school, Grossman understood wood technically — how it was sawn, dried, joined and finished.

She subsequently studied at the Högre Konstindustriella skolan (Higher School of Arts and Crafts) at the Technical School in Stockholm, completing her education in the early 1930s. This period coincided with Swedish design’s transition from historical styles toward functionalism and engagement with European modernism. Following graduation, she worked for AB Harald Westerberg, a furniture retailer on Kungsgatan in Stockholm, gaining experience in commercial furniture production and retail.

Studio at Stureplan and Early Practice

In the early 1930s, Grossman established Studio, her own design office and shop at Stureplan in central Stockholm. The venture combined design practice, furniture production and retail — a model that allowed her to control the entire process from initial concept through manufacturing to sale. Studio produced furniture and interior furnishings designed by Grossman and executed by Stockholm workshops. The work from this period shows Swedish functionalist influence — restrained forms, honest use of materials, attention to practical function — applied through her craft-informed understanding of construction.

This independent practice positioned Grossman within Stockholm’s small design community during a formative period for Swedish modernism. She was among the few women operating independent furniture studios in Sweden at this time, navigating a professional environment that presumed male practitioners. Her success in establishing and maintaining Studio demonstrated both design capability and business acumen — qualities that would prove essential when she relocated to the United States.

Emigration and Los Angeles Establishment

In 1940, Grossman left Sweden with her husband, jazz musician and bandleader Billy Grossman, emigrating to Los Angeles. The timing — during the Second World War — meant this was not a temporary relocation but a permanent transfer. She opened a new shop in Los Angeles, initially stocking modern Swedish furniture, lamps and home furnishings — establishing herself as an importer and retailer of Scandinavian design to the California market. This commercial foundation provided income while she developed design relationships with American manufacturers.

The shift from Stockholm to Los Angeles proved professionally transformative. Where Stockholm’s design culture was relatively insular and craft-oriented, Los Angeles in the 1940s offered proximity to Hollywood’s entertainment industry, a rapidly expanding middle-class market for modern furniture, and manufacturers willing to experiment with new materials and production methods. Grossman adapted quickly, beginning to design specifically for American production rather than importing Swedish work.

California Manufacturing Partnerships

Grossman’s furniture production in California was achieved through partnerships with manufacturers including Glenn of California, Barker Brothers and Ralph O. Smith & Co. These relationships allowed her to move from custom one-off pieces to serial production, adapting her designs to American industrial methods. Her furniture from this period — lounge chairs, dining tables, storage systems — shows Swedish formal restraint combined with American material experimentation and scale. She worked with walnut, teak and birch alongside industrial materials like tubular steel and bent plywood.

The collaboration with Glenn of California proved particularly productive. The 62 Series lounge chairs and sofas, produced in the early 1950s, feature minimal metal frames supporting upholstered cushions — a typology that would become standard in mid-century furniture but which Grossman approached with exceptional attention to proportion and structural efficiency. The chairs achieve visual lightness through slender frames while maintaining structural stability and seating comfort. This balance between delicacy and robustness characterised much of her furniture output and demonstrated how Swedish design principles could be translated into American production contexts.

Architectural Practice and Difficult Sites

Grossman practiced simultaneously as an architect and furniture designer — a dual engagement that distinguished her from contemporaries who specialised in one discipline. Her architectural reputation in California rested substantially on her ability to design houses for “difficult sites” — hillside lots, narrow parcels, topographically challenging locations that conventional builders avoided. She developed expertise in cantilevered structures, retaining walls and foundation systems that allowed houses to be built where site conditions appeared prohibitive.

Her first villa in Beverly Hills became her breakthrough architectural project and was published in Arts & Architecture, the influential magazine that promoted California modernism through its Case Study House programme. The house demonstrated adaptation of European modernist principles — flat roofs, open plans, floor-to-ceiling glazing — to California’s landscape and climate. She designed for hillside sites, incorporating terraces, overhangs for sun control and indoor-outdoor connections that acknowledged Southern California’s temperate weather.

Her own house on Hilldale Avenue in Beverly Hills (1950) functioned as a laboratory for her furniture and lighting designs. The compact single-story residence integrated built-in furniture, custom storage systems and carefully controlled natural lighting — demonstrating how architecture and interior furnishing could be conceived as a unified system. This Gesamtkunstwerk approach reflected her Swedish training but was adapted to American construction methods and domestic expectations.

In Sweden, Grossman designed one house: Villa Sundin in Hudiksvall (1959), a 136-square-metre residence that brought her California experience back to her home country. The project demonstrates how her practice had evolved — the house incorporates spatial strategies developed in California while responding to Swedish climate and building traditions.

Lighting Design and the Grasshopper Lamp

Grossman’s lighting designs represent her most commercially successful and enduring work. The Grasshopper floor lamp, designed in 1947, established her reputation and remains her most recognised piece. The lamp’s form — a tubular steel tripod base supporting an adjustable conical shade on a slender arm — suggests organic reference (the grasshopper of its name) while operating through pure geometric articulation. The design’s innovation lay in its adjustability and visual lightness: the lamp could be repositioned easily, its shade directing light precisely, while the overall structure maintained minimal visual presence.

The Cobra lamp (1950) pursued similar principles through different formal means. A tubular steel body curves from floor to shade in a continuous arc, the form recalling both the snake of its name and the economy of a single bent tube performing multiple functions — structural support, electrical conduit, formal gesture. Both lamps demonstrate Grossman’s ability to achieve sculptural effect through industrial fabrication, creating objects that functioned as task lighting while contributing visual interest to domestic interiors.

These lighting designs were produced by various California manufacturers and achieved substantial commercial distribution. They appeared in design publications, were specified by architects for residential and commercial projects, and entered the general vocabulary of mid-century California modernism. Their forms influenced subsequent lighting design both in the United States and internationally.

Rediscovery and Contemporary Production

Following her retirement in the late 1960s, Grossman’s work largely disappeared from view. The furniture pieces went out of production, architectural projects were demolished or substantially altered, and her contribution to California modernism was overshadowed by contemporaries like Charles and Ray Eames, whose work received sustained institutional and commercial attention. Grossman died on 28 August 1999 in Encinitas, California, with her legacy substantially unrecognised.

The revival of interest began in the early 2000s when design historians and collectors started re-examining mid-century designers whose work had been neglected, particularly women whose contributions had been marginalised. Danish furniture company Gubi acquired rights to several Grossman designs and began reissuing them in 2010. The Grasshopper and Cobra lamps, the 62 Series chairs and other pieces entered production again, marketed to a contemporary audience interested in authentic mid-century design. This commercial revival coincided with scholarly attention: exhibitions, monographs and archival research established Grossman’s significance and positioned her work within broader narratives of transatlantic modernism and women’s contributions to twentieth-century design.

Legacy and Transatlantic Position

Grossman’s career illuminates the movement of design ideas between Europe and North America in the postwar period. She carried Swedish craft traditions and functionalist principles to California but adapted them substantially to American industrial capabilities, market expectations and environmental conditions. Her work cannot be classified simply as “Scandinavian” or “California” — it occupies an intermediate position, demonstrating how designers mediated between regional traditions and local contexts.

Her particular achievement was sustaining a practice that encompassed architecture, furniture and lighting while maintaining consistent formal principles across scales and materials. This integrated approach — treating domestic environments as complete systems rather than collections of isolated objects — reflected European modernist ideals but was realised through American production methods. The work that resulted remains legible within both Scandinavian and California design histories, a testament to Grossman’s ability to navigate between traditions while establishing a distinctive position that belonged fully to neither.